In this week’s episode, we will discuss whale and dolphin watching with biologist Fabian Ritter, review breaking Dolphin News from around the world, focus our Science Spotlight on dolphin buoyancy, and in our Kids’ Science Quickie, we’ll discuss hairy dolphins.

[ms_audio style=”light” mp3=”https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/thedolphinpod3dolphinpodnews.mp3″ ogg=”” wav=”” mute=”” loop=”” controls=”yes” class=”dcp-embed-mp3″ id=””]

Mysterious dolphin deaths in Australia, Hayden Panettiere arrest warrant

A rash of dolphin deaths in Australia has biologists baffled. Sky News is reporting that nine bottlenosed dolphins have been found dead on the shores of the popular tourist area of Gippsland Lakes in Australia within the past 12 months. Researchers are unsure as to what is causing these deaths. One theory is that they are ingesting toxic chemicals which may be coming from local industry or blue-green algae blooms in the area.

*************************

An arrest warrant has been issued for Hayden Panettiere after her clash with Japanese fisherman . Hayden, star of the hit TV series Heroes, was involved in a highly-publicized protest against the annual dolphin drive hunts in Taiji Japan. This week she told E! News “I learned today that I have an arrest warrant out for me in Japan because of what I did for Save the Whales,”. Hayden stated that she was thrilled that her protest is receiving international attention.

************************

[ms_audio style=”light” mp3=”https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/thedolphinpod3sciencespotlight.mp3″ ogg=”” wav=”” mute=”” loop=”” controls=”yes” class=”dcp-embed-mp3″ id=””]

Do dolphins float or sink?

Last week’s dolphin quiz asked the question : if a dolphin stops swimming and remains motionless, will it float or sink? The answer is quite simple: it all depends.

A whole list of factors will cause a dolphin to sink or swim in water, including how much air it has in its body, the amount of blubber it has, and perhaps most importantly, how deep it is in the water. Whether or not an animal floats or sinks in water is a direct result of something called buoyancy. The principle of buoyancy was initially discovered by the famous Greek mathematician Archimedes, who was born in 287 BC. It works like this: when you submerge an object in water, the object will displace a volume of water equal to its own volume. Now, if the water that has been displaced has the exact same mass as the object, the object will stay in one place. But, if the object has less mass than the water that has been displaced, the object will float. The denser water will actually push the object up to the surface. If on the other hand the object has more mass than the displaced water, it will sink. Mass will be determined by the material that the object is made of. If you have an object made up of a very dense material, like steel, then that object will most certainly sink, whereas less dense material, like air, will float.

A dolphin’s body is filled with materials of various densities. Bones, which are denser than muscle. Muscle, which is denser than blubber. But, also air spaces – primarily the lungs. You can total all of these together to get the overall mass of a dolphin. Comparing the dolphin’s mass to the mass of the water that is displaced by the dolphin’s body when submerged will tell you whether or not the dolphin will float or sink. As a general rule, a healthy dolphin with its lungs filled with air will float at the surface: its body has less mass than the seawater it displaces. This is primarily because air is much less dense than seawater, which means a portion of the dolphin’s body volume is filled with a material much less dense than the water around it.

But that’s not the whole story. As a dolphin dives down in the water, another factor comes into play: hydrostatic pressure . This is the weight of the water itself. Water is heavy stuff, and as a dolphin starts to dive under water the increasing weight of the water on top of it will start to affects its body rather drastically. The hydrostatic pressure will cause the dolphin’s lungs to collapse: the air in a dolphin’s body is actually squeezed into a smaller area. At about 65 or 70 meters down, a dolphin’s lungs will be completely collapsed, and the actual size of a dolphin’s body will shrink. Compared to its size at the surface, the dolphin is now physically smaller – much like a sponge that you can crush in your hand into a tiny ball. But despite all this shrinking, the dolphin’s mass stays the same. Since the dolphin is now displacing less water because it has shrunk, but its mass stays the same, it actually starts to become heaver than the water it displaces the deeper it goes. So now the tables have turned and the dolphin will start to sink instead of float. This is something that all deep diving marine mammals use to their advantage when foraging in deep waters. Many species need to counteract their positive buoyancy at the surface by actively swimming down, but once they reach the magic shrinking point, they can relax and glide deeper down without moving a muscle. Not all species of marine mammals are positively buoyant at the surface: a few species of seals as well as some of the great whales are negatively buoyant at the surface. But dolphin species, as far as I have been able to determine, all appear to be positively buoyant at the surface.

Of course, this positive buoyancy assumes that they have lungs filled with air. When a dolphin or whale dies, the air in its body may disappear or even be replaced by water, causing it to sink. A few species of whale and dolphin (including the right whale and the sperm whale) appear to be positively buoyant even when dead, which causes them to float. As time passes, even the body of a dead whale or dolphin that has sunk to the bottom might actually start to float again as the process of decomposition begins creating gasses in its body that cause it to become positively buoyant.

It has also been noted that buoyancy changes depending on how much fat or blubber an animal has on its body. This may change with the season as some migratory species move from breeding grounds to feeding ground and their eating habits change.

Another factor that affects the buoyancy of dolphins while diving is the temperature of the water. In most of the ocean, the water tends to get colder the deeper you go. Colder water is denser than warm water, which means that as a dolphin starts to dive into deep cold waters, the increased density of the cold water will once again begin increasing the dolphin’s buoyancy.

So as you can see, there is no easy answer to the question ‘does a dolphin sink or swim’. But who needs easy answers when you can have interesting ones, right?

Reading Resources:

************************

[ms_audio style=”light” mp3=”https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/thedolphinpod3kidsciencequickie.mp3″ ogg=”” wav=”” mute=”” loop=”” controls=”yes” class=”dcp-embed-mp3″ id=””]

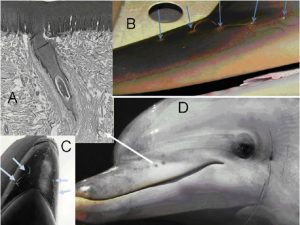

Do dolphins have hair?

As you may know, dolphins are mammals . One of the defining characteristics of all mammal species is that they have hair on their bodies. But, what about dolphins? With their smooth streamlined shapes, it doesn’t look like they have any hair at all – do dolphins have hair? In fact, when dolphins are born, you can actually find a few stray hairs poking out of their chin. But soon after birth these hairs will fall out and all you will be able to see are hair follicles which are tiny pockmarks that the hair used to grow out of. Some of the larger whales have hair that stays with them their entire lives. Humpback whales have distinctive bumps on their lower and upper jaw from which tiny hairs protrude. These hairs may actually help humpback whales to sense things in their environment, much like a cat’s whiskers. Dolphins don’t really need hair to survive: they can keep themselves warm with a toasty layer of fat under their skin (called blubber). Having no hair on their bodies makes it easier for them to swim in water. This is the same reason that Olympic swimmers tend to shave all the hair off of their bodies. Less hair equals less drag which means an easier time chasing after fish! Well, for the dolphins anyway… I don’t know if Olympic swimmers spend too much time chasing fish …

************************

![]()

[ms_audio style=”light” mp3=”https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/thedolphinpod3dolphinquiz.mp3″ ogg=”” wav=”” mute=”” loop=”” controls=”yes” class=”dcp-embed-mp3″ id=””]

What does MLDB stand for?

Last week’s winner was Allen McCloud who correctly stated that dolphins are positively buoyant at the surface but negatively buoyant at depth. Now, for this week’s quiz: Concerning a specific part of a dolphin’s anatomy, what does the acronym MLDB stand for? Think you know the answer? Surf on over to thedolphnipod.com and click on Dolphin Quiz – leave your answer in the comments section. Winners will randomly be chosen from the correct answers, and will be announced on next week’s show.

*********

Feature

[ms_audio style=”light” mp3=”https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/thedolphinpod3feature.mp3″ ogg=”” wav=”” mute=”” loop=”” controls=”yes” class=”dcp-embed-mp3″ id=””]

Responsible Whale and Dolphin Watching

According to Fabian Ritter, co-founder of the non-profit research organization M.E.E.R. (Mammals Encounters Education Research) an estimated 12-15 million people go whale and dolphin watching in more than 500 locations worldwide. Whale and dolphin watching tours can be found in over 90 countries on all continents. According to a study conducted in 2000, whale watching has a growth rate of 10-15% per year, with some countries witnessing growth rates of far more than 100% per year. This makes whale and dolphin watching the fastest growing branch of the tourist industry.

I interviewed Fabian Ritter by email about the whale watching phenomenon, and asked him about MEER’s research on La Gomera. La Gomera is the second smallest island of the Canary Islands – a group of islands located off the north western coast of Africa, and owned by Spain. Whale and dolphin watching is big business in the Canaries , with dozens of species regularly visiting the water around the islands throughout the year. According to the official Canary Islands Web site, it is the second most popular whale watching tourist area in the world, with just shy of 1 million visitors a year coming to see the whales and dolphins.

Around La Gomera, tourists can spot bottlenose dolphins, short-finned pilot whales, Atlantic spotted dolphins and rough-toothed dolphins (all resident species). Striped and common dolphins, beaked whales, baleen and sperm whales, as well as several other species also pop by for regular visits. In all, over 21 different cetacean species are seen regularly around La Gomera, which (relative to the size of the survey area) represents the highest cetacean species diversity in Europe.

But, a booming whale and dolphin watching industry does not always mean good news for the whales and dolphins involved. According to Fabian, humans can easily disturb cetaceans, primarily when watching from a boat, which is the preferred method for over two thirds of all whale watchers worldwide, or by trying to swim with them. This can cause groups to separate, change their behavior (including longer dive times, changes of swimming speed and direction, etc.), and interfere with their communication skills via engine noise, or by causing collisions, which may injure or even kill animals. These are the short-term effects.

If these short-term effects persist over longer periods of time, long-term effects may be observed (as is the case in several places around the world): Populations may change their behavioral budget, animals may abandon important (critical habitat) areas, noise and physical disturbances lead to stress and thus to a higher susceptibility to disease. This results in a lower reproduction rate and the decrease of population size.

A more indirect effect that whale watching may have is the false impression that the animals are “tourist attractions”, which “serve” humans. However, proper education and well-designed ecotours (in the sense of an education ecotour rather than a “fun trip”) may avoid the creation of such false images in the minds of visitors.

The biggest problem in La Gomera is boat-based whale and dolphin watching, as this has a far greater potential to disrupt cetacean behavior. Loud noises (e.g. fast turning propellers) and high speed boats are likely worse than slow moving boats that ideally have a propeller shrouding to prevent injuries.

Increasingly, swim-with-dolphins and whales tourism has proven potentially disruptive

According to Fabian, certain populations of wild cetaceans are already under serious threat from the whale and dolphin watching industry. David Lusseau working with bottlenose dolphins in New Zealand has found that the small population in Doubtful Sound is threatened to disappear as a consequence of unsustainable tourism practices. Also, Lars Bejder and colleagues found a significant effect on the reproduction rate of female bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia .

Fabian suspects that the cetaceans off of Tenerife (another island in the Canary Islands), which probably are the most intensely watched cetaceans in the world (up to 30-35 boats going on 2-3 trips every day, or over 10.000 trips per year) will have difficulties thriving in the long term, although there is no scientific evidence yet to suggest that long-term damage is occurring.

Currently, there is no universal standard, code of conduct, or regulatory body that oversees whale watching operators worldwide, although there are national regulations for some countries involved in whale and dolphin watching. Fabian suggests that the general attitude should be that humans should adapt our behavior to the needs and habits of the animals; that is so that the animals can avoid having to adapt theirs. And, that whale and dolphin watching tours should be promoted as a way to experience nature and to learn about it, rather than inflicting our desires onto nature. The management of the industry should be pro-active following the principles of sustainability with the establishment of properly enforced legislation dictating a maximum number of operations per area and time unit, a limit to the number of boats, as well as a set of rules of how to behave around the animals, and constant monitoring both of the populations and the effectiveness of the rules/regulations themselves.

Above all else, Fabian feels that common sense, sensitivity and experience are the most important tools to deal with cetaceans in a proper, i.e. sustainable, or better to say respectful way.

Wrap-up:

That’s it for this week’s edition of The Dolphin Pod – thanks for tuning in. If you would like more information about the stories from this week’s episode, check out thedolphinpod.com. If you’ve got questions or comments about this week’s podcast episode, please contact us through the website. Why not consider signing up for the Dolphin Communication Project’s online community? You’ get access to a forum where you can discuss the The Dolphin Pod with other listeners. The DCP website offers a chance to adopt one of our dolphins from the Bahamas, as well as learn more about volunteer, internship and ecotour opportunities.

Don’t forget to join us next week for more dolphin science news and info. And remember, the dolphin pod is only a click away.